When I entered her hospital room in Cape Canaveral that day in mid July of 2020, I hadn’t seen my mother in over a year, and before that, rarely. I was going for estrangement; she was clawing for reconciliation. But reconciliation for my mother meant bringing me back under her folded wing where she could peck at me with abandon without any complaint from me.

|

| My mother at about age ten |

For most of my life, I didn’t consider my mother an abuser. Child abuse, so many assume, involves violent beatings or sexual exploitation. Medical and psychological professionals, naturally, recognize emotional and psychological abuse as destructive, but even then, the general public imagines such abuse must be vicious and obvious to any observer.

Even after I understood that my mother didn’t love me, that she was incapable of love, it took quite some time for me to understand that what she’d done to me was actually abuse. No one outside, looking in, would think it. My mother didn’t break any bones. She didn’t scream obscenities at me. She never came right out and told me she hated me, or that I was worthless. What my mother did to me was much more cunning.

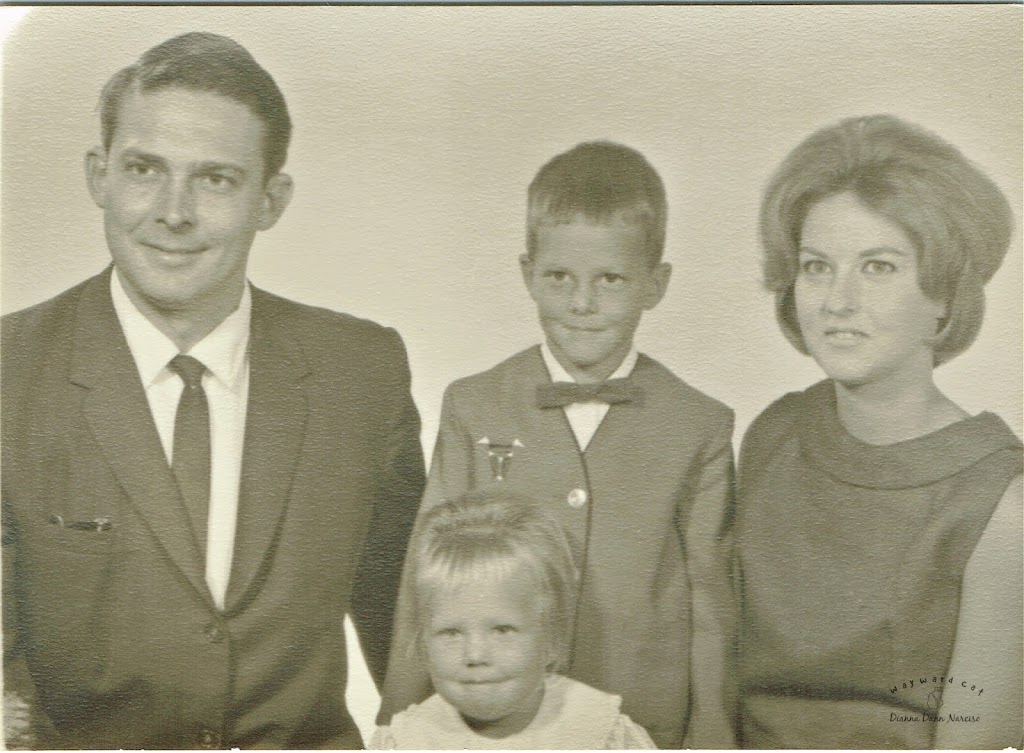

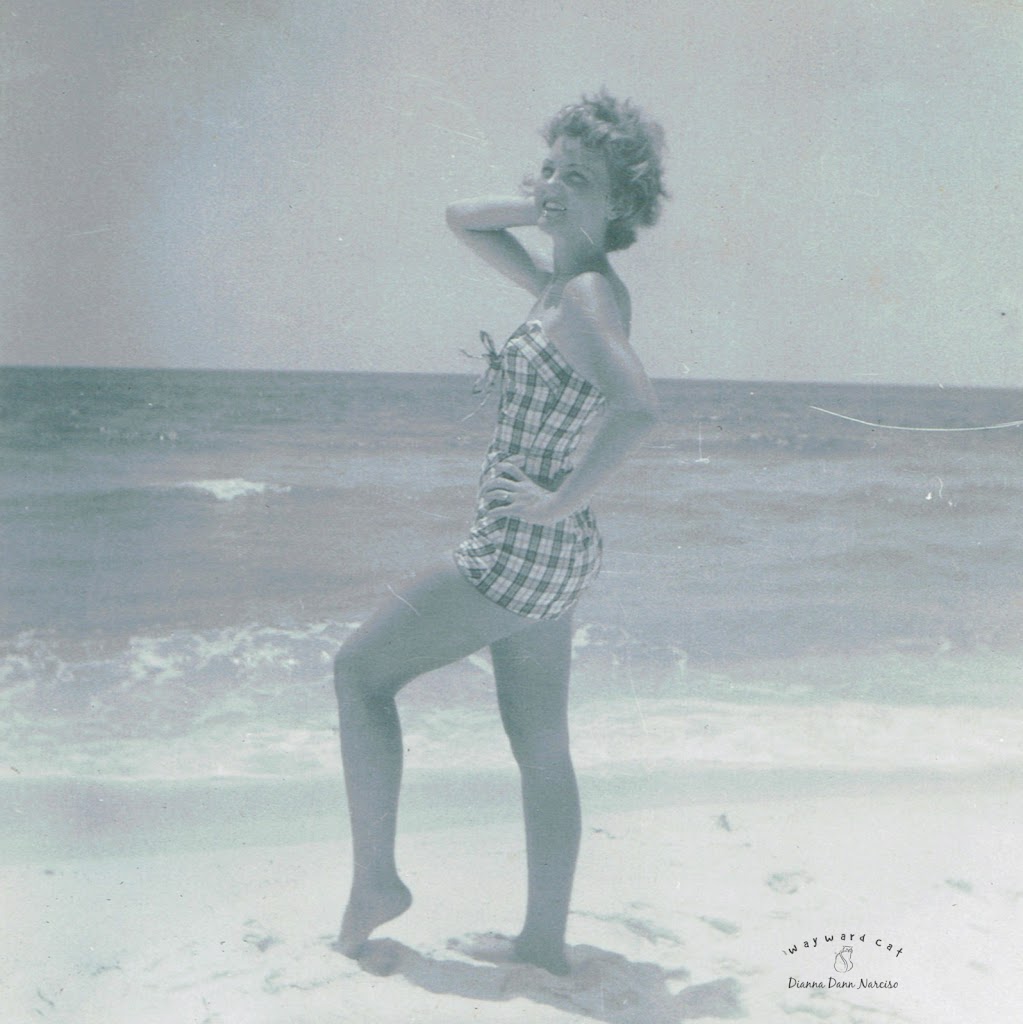

|

| Watch me slip away… |

Inevitably, when you talk about childhood abuse, someone will point to others who suffered as well, but who grew into self-actualized, healthy adults. They use these examples as evidence that if you are suffering, it’s because you aren’t trying hard enough to heal. This is survivors’ bias. People who descend into drug abuse, criminality, anti-social behaviors, or extreme depression are sometimes accused of wanting to remain mentally unstable. I’ve heard people actually say that some victims enjoy wallowing in their misery. The “happiness is a choice” mantra is destructive (and bullshit).

No one’s story is the same. No abused child can be compared to another. Circumstances, abusers, family, schools, resources—there are so many variables in a child’s life that come together to determine how she will respond to abuse. Never let anyone else tell you how you should feel, how to heal, or how long it should take. The best you can do for yourself is to find some small number of others who understand you and refrain from trying to explain yourself to anyone outside of that group.

My mother broke me. She ruined me. Anything good in my life now is despite her, not because of her. I now walk a fine line between longing for what might have been and wanting to retain what joys I currently have.

Imagine if I’d been raised by a loving mother and father (because my father is not blameless here). I might have had self-esteem and a healthy self-image. I might have been as mature as my schoolmates. I might have had healthy friendships and relationships. I might have learned discipline. I might have gone to college out of high school—I don’t doubt I would have. I might have had a career.

But had I done those things I most certainly wouldn’t have met my husband and had the children that I have now. I would not trade my childhood for their existence, but I would have liked to have been a better mother.

Not wishing for a different life doesn’t mean I owe my mother gratitude or thanks. I don’t.

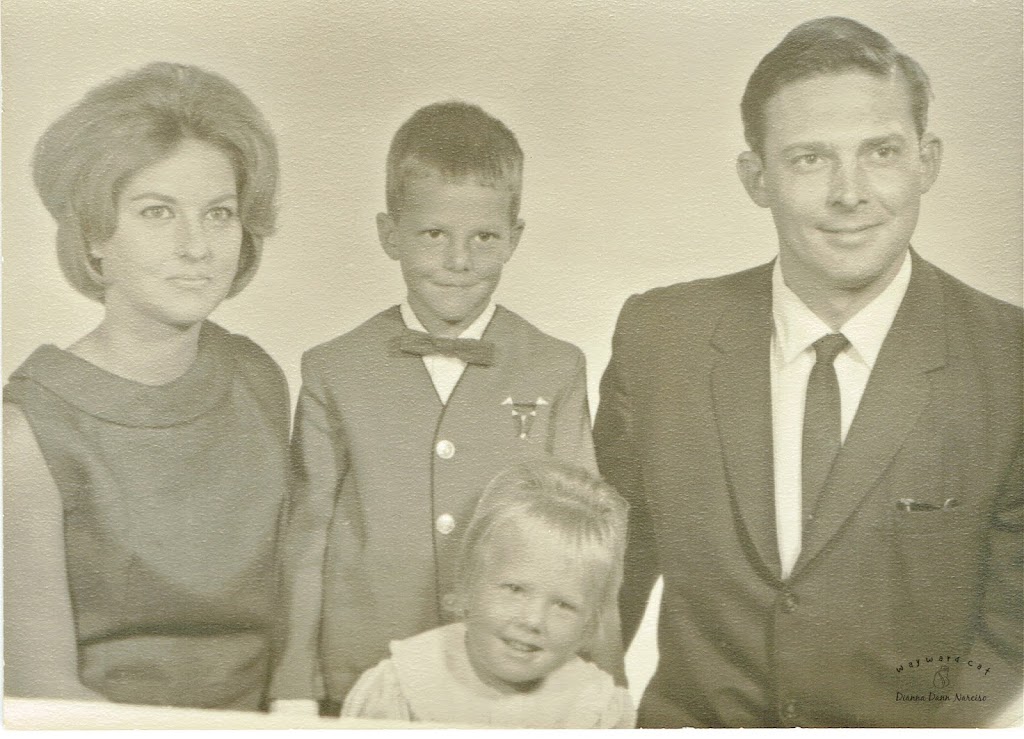

|

| My mother at age two |

My mother was a covert narcissist. This means that to others all around us, she was a sweet, devoted mother and my behavior was out of line. I was bad. I was at fault. There was something wrong with me. There was no adult in my entire life who saw what was being done to me—if they saw they did nothing. My father did nothing. No extended family member, no family friend, no teacher, no school counselor—no one—did anything to help me and in fact, did much to harm me. Eyes rolled. Criticisms were made. Tongues were clucked. No one ever stopped to wonder what was happening in my home that might make a child behave in such a way—inability to speak when spoken to or criticized; uncontrolled weeping; torrents of rage; stealing; lying; compulsive skin picking. Why would a child of six, eight, or ten behave this way? Why do we always look only at the child when no bruises are visible?

Well, how could anyone look at my mother, with her doe-eyed worry, her wringing hands, and her pleas for understanding, and think any of this could be her fault? As far as the world was concerned, I was raised in a loving, healthy, upper middle class, nuclear family. My mother was beautiful and charming. My father, handsome and jovial. My brother was popular, good-looking, athletic, and talented. I was a problem child.

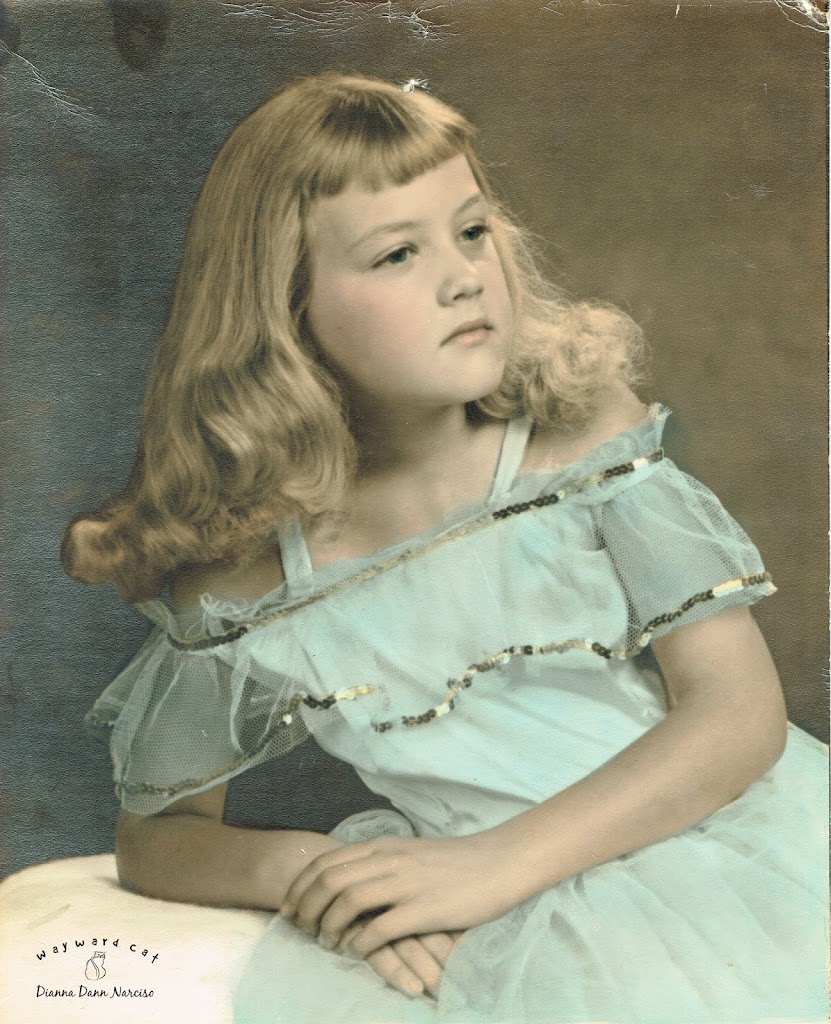

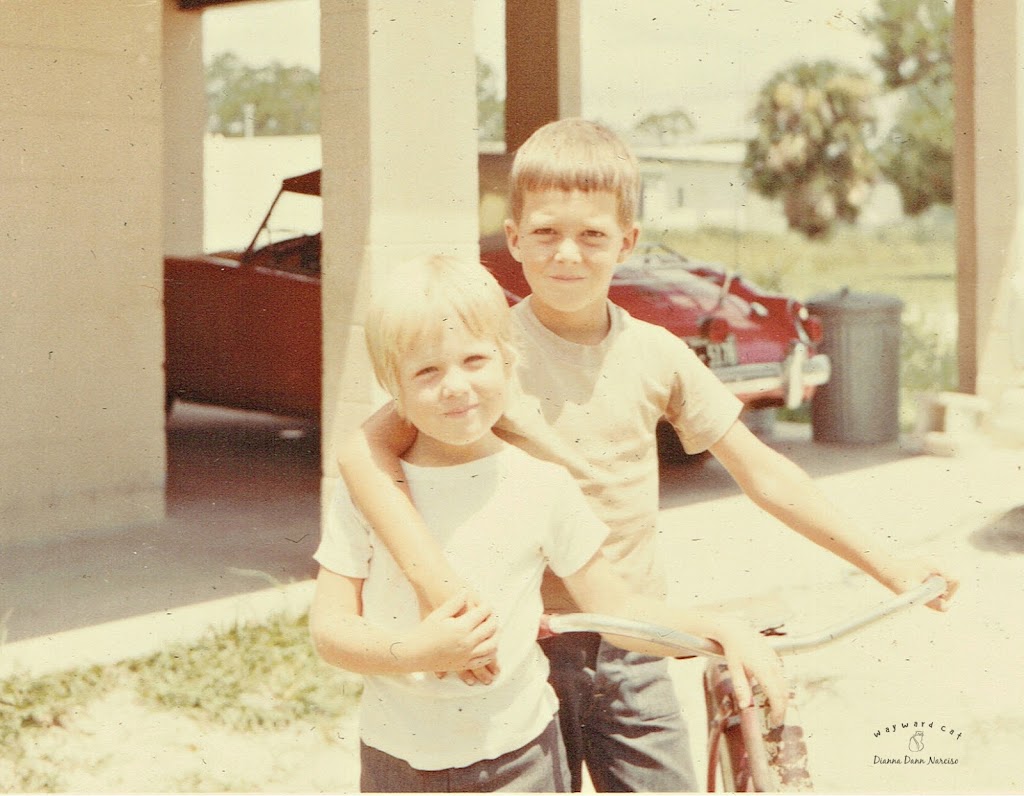

|

| My mother and me |

Other daughters of narcissistic mothers will recognize this family dynamic. My mother was the abuser. My father, her enabler. My brother was the Golden Child. And I was the Scapegoat. Lucky me.

My father, if you asked him now about my childhood, would shrug and say something like, “I thought we were a happy family.” My brother only began to understand what happened after years of struggle between my mother and me that finally ended with me admitting to him some of what I went through. And to his credit, he understood. With the weight of manipulation my mother poured onto him, the Golden Child grew into the dichotomy of a man filled with both empathy and anger. This comes to me as no surprise.

My brother was ever the only person in the world to care for me. Any self-esteem I have, any positive self-image, any knowledge of what it is to be loved came from him.

My brother took care of my mother his entire adult life. Before she and my father divorced, he unwittingly attended to her self-esteem by loving her unconditionally and feeding her ego. After the divorce, he tended to any needs she might have. At first, my mother managed to live on her own for quite a while, but as she grew older, my brother was at her beck and call—mowing her lawn, seeing to repairs around her house. Your first thought might be, but of course. And you’d be correct. Except that with my mother, she began to refuse to do more and more for herself and expected my brother to do anything she didn’t want to do. And she wasn’t forthright about it. She played games, acted helpless, and then smiled and bragged about how she’d played him.

My mother, throughout her life, had an enormous sense of entitlement.

As she became more and more feeble, his burden grew until he was picking her up off the soiled carpet in her apartment and calling for an ambulance…more than once. Early on, these episodes were driven by alcohol and prescription drugs, later perhaps it was the cancer.

Disentangling myself from my mother’s abuse was a gradual process and took decades. But in later years, when I had pulled far enough away from her emotionally, she had no one to abuse, so she turned on my brother. This is not to say she hadn’t been nagging and pecking at him his entire life. But it had always been done under that covert haze of “for your own good” and “I’m only trying to help.” Once she got to a particular age, with a certain level of mental decline, she failed to keep her cruelty in check. The covert in her narcissism fell away and she started abusing him to his face. And he was appalled.

|

| My brother and me |

Late last year, after another fall and an inability to get back up, my mother was diagnosed as having a large tumor on one of her ovaries. Medical opinion was that if she was still alive and well three to four months later, it was nothing more than a “complicated cyst.” There would be no biopsy because if it was cancer, a biopsy could make it spread faster. And both my mother and her doctors agreed that she wouldn’t likely survive surgery and chemotherapy, anyway. So my mother waited and prepared to, as she put it, meet her maker.

Six months later she hadn’t changed so my brother believed that she didn’t have cancer and would, as they sometimes say of mean people, outlive us all. But nine months after the diagnosis, the truth started to sink in. He told me she was deteriorating badly and if I wanted to say my good-byes I should visit her. But the COVID-19 pandemic had hit Florida and not only did I not want to die, I didn’t want to risk killing my brother, so I didn’t visit my mother. How much of this was merely an excuse to avoid seeing her, I can’t say.

Then, in July, my brother told me she was in the hospital again. She’d do this the whole time, he said. She’d get very weak and sick, go into the hospital, get better, and go back home. This time she was vomiting and couldn’t get out of bed. He assumed she would either get well enough to go home, or end up in a nursing home. But after two days in the hospital, the hospice nurses explained to him that this was it—she had only days left. And my brother was heartbroken.

When he contacted me again, he said he didn’t want to pressure me at all. But it would be helpful to him if I would visit her. Because of the pandemic, only one person was allowed to visit each day, and he was struggling with seeing her there, knowing her end was near. I have to say, I don’t recall ever in my life hearing my brother cry until that week.

So, I visited my mother.

|

| My mother |

In the circles of daughters of narcissistic mothers, there are those few who come at the rest of us with a warning about not reconciling with our mothers before they die. “You’ll live the rest of your life with regret if you don’t!” they scold us. But the majority don’t take the bait. There are mothers out there who have done horrible things to their daughters, things that make my mother look like a wonderful person. Narcissistic abuse can be devastating to the human psyche; it takes many forms and is doled out in varying degrees depending on, at the very least, how sick the narcissist is.

I never felt that I would be guilt-ridden if I never saw my mother again. I vowed, after realizing that what I suffered was psychological and emotional abuse from birth by my mother, and at the very least emotional and psychological neglect by my father, that I would do what I felt was best for me. I’d already spent untold hours of self-reflection, attempts at relationships with my parents, counseling, and struggling for mental health. I’d come to terms with the fact—FACT—that my mother did not love me. That she didn’t even like me. And so I was prepared to accept that my parents would die without changing. Because they were incapable of change. And I refused to allow myself to be in a position where they could abuse me further.

With that in mind, I decided that I would visit my mother as she lay dying. Not for her. But for my brother. And for me…because I felt that it was the kind thing to do. And honestly, I trusted that she was in such a weakened state, she could do little to hurt me.

I think the worst thing about being unloved as a child is that most people refuse to believe it’s possible. It’s no wonder our children’s bad behaviors are so often laid at their feet and not the parents’. Parents love their children. Of course they do. It would be unthinkable otherwise. Human beings are, after all, hardwired to love their offspring.

Well, I and many other unloved children would like a word.

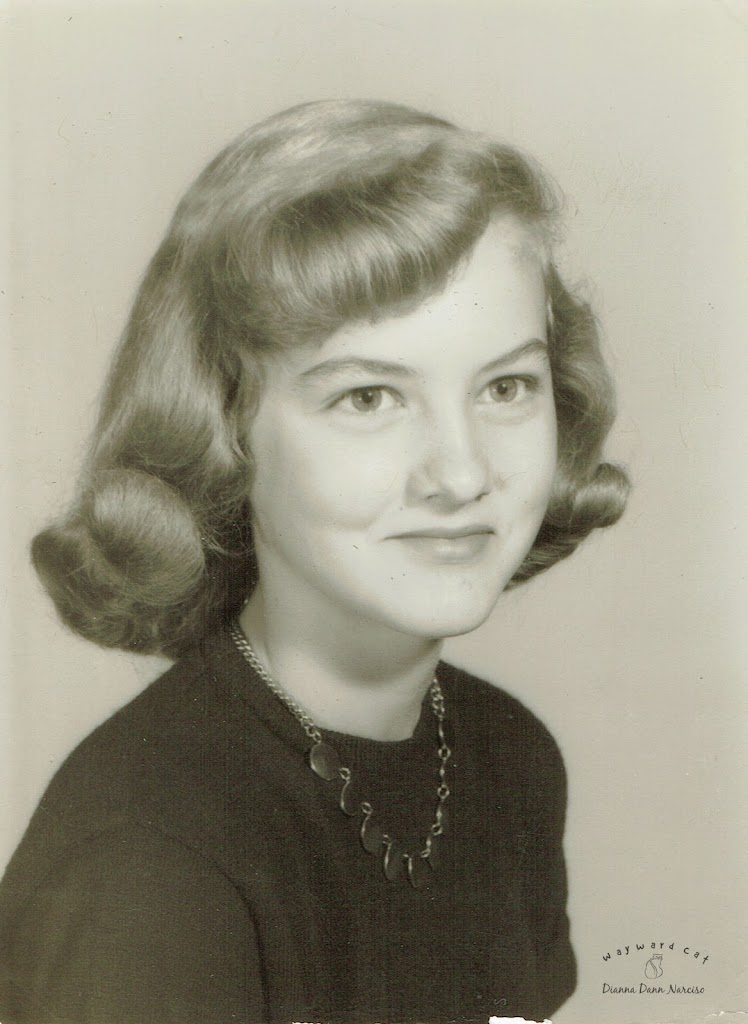

|

| My mother in high school |

It’s frustrating to be told by so many people—even after you’ve explained the situation—that your mother loved you. Sometimes they’ll tack an “in her own way,” or “despite it all,” to the end of their ignorant proclamation. They have to believe that mothers love their children. At the same time they know that sociopaths and psychopaths exist. Do they truly believe that psychopaths are capable of love? They’re not.

When I first imagined I’d been unloved as a child, I was in my mid-twenties. While I was relieved to find that the destruction I’d been hurling at myself through my teen years and beyond had a cause, an impetus that I could get to and work out, I also sensed that what I’d been feeling would never really go away. There would always be, I was sure, a pit deep within that was supposed to be filled with love but was left empty. You can’t go back and fill it yourself. By the time your childhood is over…it’s too late.

Still, I held out some hope that maybe I was wrong. Maybe my parents’ love was just not quite enough for me. Existent, but muted. Perhaps I was difficult. They were merely unable to handle me the way I needed handling.

Then I had children. That was when I knew for sure. There is no way my parents could have loved me and treated me the way they did. I was going to have to learn to live with that blank, gnawing space—the wound that never heals.

People who cannot feel or express empathy cannot love. The ability to feel empathy runs along a scale, of course, and narcissists aren’t all psychopaths. My mother certainly wasn’t. But she lacked enough empathy to really love. For my mother, love was about her fears of being unloved and found out. She expressed love in words only—with perhaps an occasional attempt at actions that she thought suggested it—as attempts to either hear the words directed back at her to chase away her fear that she was unloved and unlovable, or to be seen as a good mother who, of course, loved her children.

My mother desperately needed me to love her. But I realize now what my childhood was all about. I see it so clearly—the fear, the uncertainty, the doubt. I instinctively knew I wasn’t loved. Or the love my brother gave me was ample enough to teach me the difference. So I never did love my mother. I went from need, to fear, to hatred, to resentment, to disgust, and finally to pity. But love was never on the table.

My brother loved my mother a great deal. For him, her showers of praise and adoration were enough of a substitute for real love. Coupled with the appreciation of, and kinship with, my father, my brother had a great childhood. When he spoke, he seemed to be understood. His emotions seemed to be respected. He felt as if he was heard.

I hate to tell him that what he experienced was not, in fact, love. Not at all. Coupled with the joy my mother expressed basking in his reflection, was her manipulation of his emotions. She undercut him at every turn toward independence. She worked on him over the years until he felt a deep sense of responsibility for his mother’s happiness, and guilt when he couldn’t succeed in making her so. What my brother thought of as love was actually my mother feeding off the illusion that she was a wonderful mother because she had such a wonderful son. And anything he did that might crack that vision was set upon—subtly cruel at first, then through nagging, criticizing, and insults. She used all the tools she had.

|

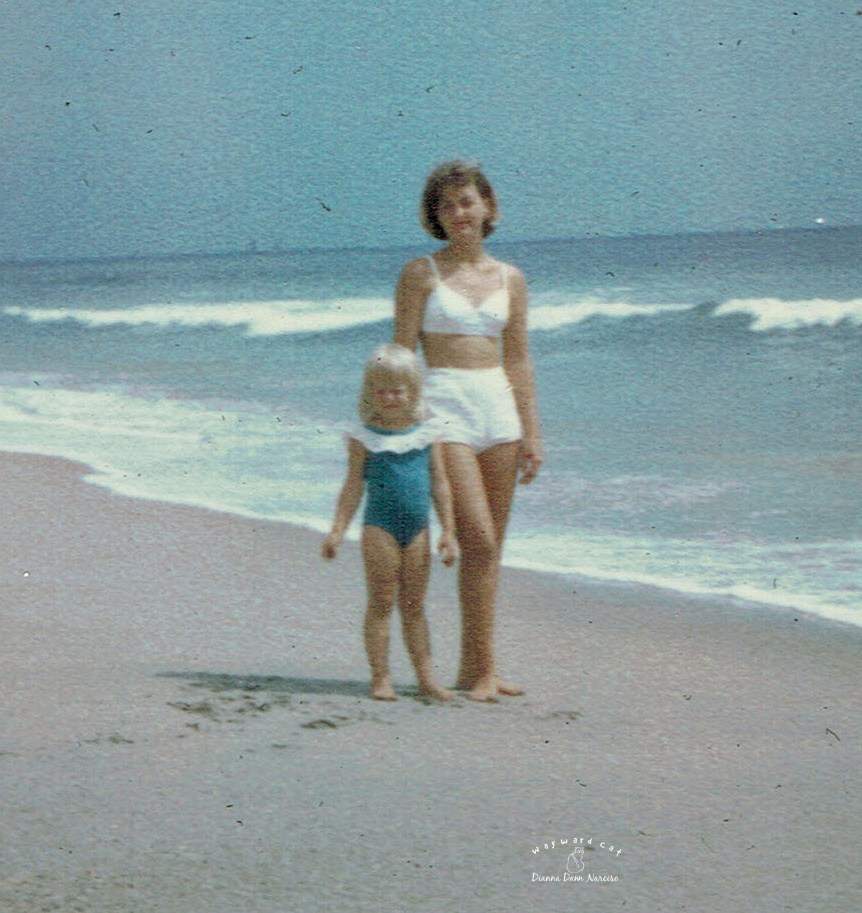

| My mother: A portrait |

For whatever reason, my mother disliked women and girls. And I was, unfortunately, a girl. A rather frumpy, unattractive little girl at that. But had I been born male, it’s unlikely it would have made a difference. Someone, daughters of narcissists will tell you, has to be the Scapegoat. Someone has to take on all the ills of the family so that it can maintain its idyllic illusion to outsiders. The family is perfect, you see. Look how charming it is, how loving it is. How happy they all are. Ignore that child in the corner trying to pull her lips off. She is necessary but not important.

I know it doesn’t make sense. Not to people who had actual loving families.

When I walked into her room at Cape Canaveral Hospital, in the hospice unit, the nurse woke her up and when my mother saw me, I knew she was happy and relieved. The Prodigal had returned. To the hospice nurses, I’d granted my mother’s dearest wish—a patching up of our relationship. I didn’t tell them there was no relationship to patch.

I was reminded of a time several years before, as I was pulling away from her, extricating my self-esteem from her abuse. She said to me, “I just don’t understand when things got so bad between us.” This was my mother’s view of love in a nutshell. When I was a child of ten, I was obedient and cowed by her. She thought that was a loving mother/daughter relationship.

I was shocked at the look of her. Gaunt and gray. Bones and skin. She said she loved me and I told her I loved her too. Why not? I thought. What harm could it do? She tried to talk to me and I told her there was no need. “We’re good,” I said. “No need to say anything.”

I lied. But in that lie I realized that I was there for more than just my brother. And I was there for more than just myself—as a talisman against self recrimination. I was actually there because a woman that I’d known my entire life—one I didn’t really like, who didn’t like me—was dying. And she had no one else to sit with her. So I did.

I read my mother poetry, two poems especially that I thought were her favorites. I read them both several times over the next few days sitting at her side. I read her some of a book by one of her favorite authors. Hell, I even read my Twitter feed after I tired of everything else. I played her music and videos on my phone—The Sound of Music and songs from the film. If I Were a Rich Man and Sunrise, Sunset from Fiddler on the Roof. I reminded her of our trip to Europe. I talked about her cat. I told her all about my husband and children. She managed to say, “Baby?” when I mentioned my oldest son and I told her, “Not yet, but maybe soon.”

That first day, she was alert and listening and responding and held my hand tightly. The second day she was alert only once in a while and barely squeezed my hand a few times. The third day…I don’t think she was there. But I talked and read and played music just the same. The first day, I played Pachelbel’s Canon from my phone and cried. She was watching me and I said, “This song makes me cry every time.” On the third day, I played it from a CD collection I’d brought and I stared out the window at the inlet and a pier with a covered gazebo and I didn’t cry at all.

|

| The view from my mother’s hospice room |

On Friday, July 17, neither my brother nor I could visit. It upset me that she might spend an entire day without family. But I was relieved that my mother’s sister would do it, though I couldn’t be sure if my mother would have wanted it.

My mother used to complain about her own mother and the way she would play all the family against each other, causing arguments and division. And yet, my mother did the same thing. Immediately after her diagnosis, while the reality was still uncertain, she did all she could to have everyone come to her rescue, to do her bidding. My mother loved nothing more than having everyone “do” for her. Once, before she showed any signs of illness, she called hospice and claimed she’d fallen, but when the nurse showed up, she managed to talk the poor woman into doing the dishes for her.

My mother allowed a former in-law to ingratiate herself into those final months. And she told this person, and her sister and others, that my brother wouldn’t take her to the doctor, didn’t want her to get treatment for her possible cancer, and was abusing her. Nothing I could say to these people made any difference. They believed my mother and at one point literally accused my brother of not wanting his mother to live.

My brother, who cared for her throughout his life, who took her abuse as best he could, who continued to care for her daily even while she smeared him to others and he knew it—they accused him of not taking care of her. This caused irreparable damage to family relationships.

I know some would say that my mother was ill—narcissism is a mental illness. And I shouldn’t feel ill will toward those she conned. But it’s not so much that they believed ridiculous and horrible things about my brother—and about me, for that matter. They allowed, however unwittingly, my mother to abuse me, and worse, took part in it. I was teased and scolded, as a child, for things beyond my control. It’s difficult to separate my childhood from my extended family. I didn’t just leave my mother, after all. I left the family. I’m estranged from it all.

But through this experience, I’ve come to realize that you can’t force anyone to see the truth. You can’t make someone believe you. You have to stop caring what others think about you, about your choices, decisions, actions. You have to do whatever is necessary to allow yourself to heal. And those who care about you will understand. Those who don’t, well, you were right to walk away.

There will always be those who think I was a bad daughter because I left my elderly mother in the care of my brother. Because I didn’t visit her, clean her house, cook for her, tend to her. It was my duty, they’d say. They’re wrong. It’s not a child’s job to love her parent. It’s the parent’s job to love her child. And if my mother had loved me, she’d have had me there at the end, loving her.

I did my best as a human being who feels empathy for a dying old woman. That’s all. What I managed to do is enough for me.

I recently finished reading Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. This haunting story revolves around Lily Bart, a character you very much want to cheer for. You want her to realize her mistakes, come to her senses, make the right choices. But she never does. And in the end you are empty with the thought that she lived her entire life searching and never finding and you feel as if it was a waste. A waste of a life.

That’s what I thought about my mother. In my mind, she was always grasping and clawing for something better. She never seemed to get past the reality that she had to do things for herself—that the world was not put here to serve her needs. She lived her life constantly feeling unjustly treated by anyone who didn’t praise and serve her. She was never able to see her own hand in her undoing. She didn’t know. As much as I often think of her as a willfully cruel person, I do understand, at least intellectually, that she was like Lily Bart in one way—she couldn’t see what she was doing to herself and to others.

For whatever reason, my mother was a narcissist. She didn’t know it, couldn’t conceive of it. She was incapable of self-reflection. Anything negative a person might say about her, she turned back onto them. She was a gaping hole that needed constant filling with praise, adoration, and subservience. She didn’t do what she did to me on purpose.

That really changes nothing, however. For me. So I am left only with the consolation that I have managed to be as mentally and emotionally healthy as I can be, and that, when the time came, I was kind to someone who was rarely kind to me.

|

| Dianna Cole 08/23/1938 – 07/17/2020 |

After my mother died, my brother and I cleaned out her apartment. I gathered up her journals and photographs. And I took a few great books from her shelves. One was the complete poems of Robert Frost with two bookmarks in it. She’d kept the place of those two poems I read to her again and again as she lay dying. The Road Not Taken and Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.

I’d been right. I did good. I hope that gave her some peace.