Gone With the Wind, the Confederacy, and why we are in the mess we’re in now…

Well, I did it again. I read Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell. This was my 21st reading of this book. You might wonder how a person could possibly read such a book twenty-one times. It’s easy when you’re old.

I first read GWTW at fifteen after I saw the film in the theater. No, I wasn’t fifteen in 1939…duh. I guess it was a special showing. And what do you know, GWTW is showing at a theater near me next week! Hmmm… I see more reminiscing in my future.

I was smitten. The dresses. The mansions. The dashing heroes. There was a time when I thought the ultimate delight would be to be rich enough to have a theater in my home where I could screen Gone With the Wind anytime I wanted. When VCRs were a thing, my dream pretty much came true. And of course, I own the film on VHS and DVD.

Anyway, I got the book for my birthday in December of my fifteenth year and had it read by year’s end. How is that possible, you ask? Simple, I skimmed that 1024-page novel like a hungry raccoon digging through the neighbor’s trash looking for the romantic bits from the film. I skipped all the boring parts!

Then I read the book again every summer for sixteen more years, continuing no doubt to skip boring parts until I was well into adult-hood. After that, I read it a few more times when I had the chance. And here we are. The twenty-first reading of Gone With the Wind.

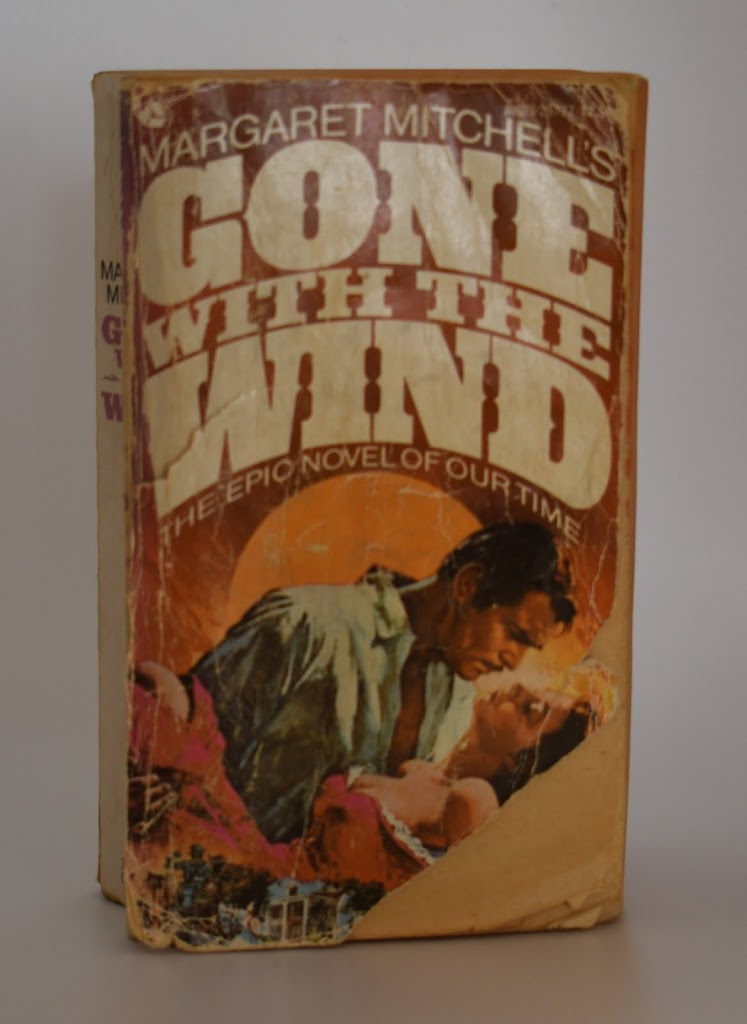

|

| My original copy, now battered and delicate. Printed in 1973. |

The last time I read it, I told my husband that I was surprised at the freethought contained in it. He accused me of reading into the story what I wanted to find. How insulting! So, this time I read the book on my Kindle and highlighted every instance of freethought I found. I think there was one. It’s clear that Rhett Butler is an atheist and I suppose I was surprised that his lack of belief in a deity was so casually handled in a book written in the Thirties. Scarlett O’Hara is less of an atheist than she is a convenient believer. So, maybe we’ll let my husband have this one.

I wanted to write about the book because a lot changes when you age from fifteen to fifty-eight. So, here we go. I’m going to get into the racism and ignorance of the South in a minute, but first…

Characters.

The characters are no longer who I thought they were.

Scarlett O’Hara is an anti-hero throughout the book. I’ve always recognized that. She’s a shallow, selfish, emotionally stunted girl who grows slowly, unwillingly, into an adult. Well, maybe slowly isn’t right. She rejects thoughts and emotions that threaten her stubborn hold on a false reality until the very end when, in one fell swoop, she finally sees reality and grows up.

Up until that moment, however, she’s infuriating.

It’s hard to fault Scarlett. The war broke out when she was a mere sixteen–a belle of the county–and her world was turned upside down. She clung to some selfish traits for survival’s sake.

Scarlett isn’t all bad. She’s the strongest and smartest person in the entire novel. She refuses to buckle under and starve while the rest of the South clings to honor and decorum. She doesn’t shy from hard, dirty labor and insists others in her family work too. They fail and Scarlett takes up the slack…all the time. It’s because of Scarlett O’Hara that Tara survives the war and becomes a profitable farm by the end of the story. True, there was some luck in that the plantation house wasn’t burned (though it was set on fire at one point). But you come away from a reading of Scarlett feeling the she’d have rebuilt the damn thing if the Yankees had demolished it, so forceful was her will.

Scarlett O’Hara also has a strong moral code, though she herself doesn’t recognize it. She believes that she stays with Melanie Wilkes in Atlanta during the siege, and then carts her and her baby, half dead, all the way to Tara before Sherman takes the city, because she promised her beloved Ashley that she’d take care of his wife.

But that’s bullshit. Anyone who reads the entire novel can see that Scarlett has an idea of who her people are and she fights for them, works her fingers raw for them, and takes care of them…even when she doesn’t like them much. Scarlett doesn’t like her sisters and with good reason. Suellen is spoiled, refusing to pick cotton because it’s beneath her, caring nothing for Tara. And Careen is a girl with her head in the clouds who will never come down to earth and ends up in a convent.

Scarlett thinks she hates Melanie Wilkes and at every point in the book where she has an inkling that she doesn’t hate the woman, she stifles the thought because she believes she loves Ashley Wilkes and therefore, she must despise Melanie. In the end, she knows she always admired Melanie Wilkes, but was too stubborn to let herself admit it. Melanie is her family–her sister-in-law–and therefore, Scarlett takes care of her.

And let’s talk about Melanie. The woman is stupid. She’s portrayed in the novel as a great lady–kind, moral, honorable. But she’s not. She’s kind, yes. And admirable in many ways. But let’s take a look at her morality.

Melanie argues strenuously, threatening her position in Atlanta society after the war, for weeding and caring for the graves of Yankee soldiers alongside those of Confederates. But, why? Is it because she sees worth in all lives? Nope. She does it because there are Confederate dead in the North, too, and she hopes that some kind Yankee woman (“There must be one kind Yankee woman!”) is caring for those graves. She has to care for Yankee graves to keep her hope alive that a Yankee is caring for Confederate graves.

Later in the book, Melanie makes it very clear that she hates Yankees. Literally. Hates them.

So, sure, I suppose in the Southern, Confederate, slave-holding mindset, she was a great and honorable lady. She was kind. And sweet. I’ll give her that. She was also strong and fierce and Scarlett comes to recognize that by the end.

The problem is that Melanie can’t see that Scarlett does what she does, not because she loves Melanie, but because her moral code dictates it. Yes, yes, Scarlett comes to realize she loves the woman in the end, but she spends the entire novel in love with Melanie’s husband. Melanie is blind to it all.

And about that husband!

Ashley Wilkes is given to us–and I mean as society and the film industry has decided, not by Mitchell–as a paragon of honor and virtue. But the man is a cad! He lusts after Scarlett even while married to Melanie. He strings her along, courting her as a young girl, telling her he loves her several times–even when married–kisses her, tells her he wouldn’t be able to control himself if he were alone with her again, on and on. The man’s a complete douche. Scarlett finally recognizes that he’s worthless and she was in love with a fantasy all along.

|

| Just some of my GWTW collection of stuff. |

And she loves Rhett Butler, after all.

We like to think of Rhett as the scoundrel who turns out to be lovable and honorable. Bullshit. Utter bullshit. The problem with Rhett Butler is this: He marries Scarlett knowing she’s emotionally stunted, knowing that she thinks she’s in love with another man. Then he belittles her, mocks her, sets her up time and time again knowing what she’ll do only to take great pleasure in knocking her down. Worse, he betrays her. When he decides to reform his image in Southern society, he pretends to be ashamed of Scarlett’s business sense and success, even to her family, further lowering Scarlett’s reputation among the old guard.

But the worst thing that man does is in the end. He has the gall to put the blame for the end of their marriage on her and only her. She killed his love for her and now he’s leaving. He’s awful.

It’s probable, however, that now that Scarlett has finally matured, he’ll be back. And maybe those two–both petulant children throughout the book–will work it out.

Now, about the racism.

Oh, my god!

Some might claim that Margaret Mitchell was only showing racism through the eyes of her characters, but it’s not true. In one instance–and that’s all it takes–she speaks not in any character’s viewpoint, but as an omniscient narrator, about Mammy, comparing her to an ape. Blacks are compared to apes in at least one other instance, and they are characterized as childlike and stupid. Here is one part that is particularly damning:

Sam galloped over to the buggy, his eyes rolling with joy and his white teeth flashing, and clutched her outstretched hand with two black hands as big as hams. His watermelon-pink tongue lapped out, his whole body wiggled and his joyful contortions were as ludicrous as the gamboling of a mastiff.

This is straight out of blackface and minstrel shows. Cringe-inducing.

Unfortunately, there’s more. In GWTW, the ridiculous Southern Confederate trope of the benevolent slave owner is king. Even the slaves parrot this notion. Big Sam begs Scarlett to send him back to Tara. He wants no more of freedom. He wants to be told what to do and when to do it. And he wants to be cared for when he’s sick. He says that the Yankees he met when he traveled north were always asking him about beatings and torture. But he knew that “Mr. Gerald” would never hurt an expensive–and here he uses the N-word in reference to himself–like him.

But we expect racism when we read Gone With the Wind. It’s set in the South during the Civil War and Reconstruction. There’s going to be racism in it. If that racism was explored only through the characters it could be argued it was acceptable. But it’s not. And there’s no counterbalance at all–nothing about the book looks into the subject of slavery and rebellion in anything but blissfully ignorant terms.

I should mention here that there is also a slur against Jews in Chapter Forty-one. But of course. Am I right?

There were attempts at kindness in the way in which Scarlett treats some of her servants. She does seem to love them. And if we were merely looking at a character raised to look at blacks this way, we might be able to stomach it. But nowhere in the book, not in any character, not in any scene, is there any hint that slaves and former slaves were thought worthy of freedom. Nothing about their humanity, their value as individuals. Never a mention as to the vile inequality and exploitation of the institution of slavery.

There were a few instances in which Southerners were apparently not entirely pro slavery. There is a mention that Frank Kennedy, Scarlett’s second husband, and many of his friends didn’t “believe in slavery.” But they believed that the hiring of convicts–because the Freedman’s Bureau wouldn’t be monitoring how you treat them as they would with freed slaves–was somehow “far worse” than slavery…than the literal owning of another human being.

At one point, Ashley Wilkes claims he would have freed all the slaves at Twelve Oaks when his father died, if the war hadn’t freed them. It was pretty easy for him to say that now that the war was over, but was it even true? Possibly. But Ashley Wilkes was a man of books and leisure. He had no head for business. The idea that he’d put the plantation in peril by freeing the slaves is doubtful.

But the most infuriating thing about reading GWTW this year was the constant whining by the Southerners about how mean the Yankees were treating them. They weren’t allowed to vote unless they signed a pledge! They couldn’t run for any government offices!

At no point does any character consider that they just got finished mounting an insurrection against the United States of America. They were traitors to the country that defeated them. And yet they truly believed they should have the right to run their states the way they pleased and be left alone.

The South has never gotten over losing the Civil War and they were allowed to slither back into the Union without truly being defeated. Their racism, misogyny, and ignorance has continued to infect a large portion of our population to this day.

It’s not an easy book to read and I came away from it saddened by the way in which Margaret Mitchell and others like her created the sacred myths of the South and the Confederacy.

The way of life that was mourned throughout the book was grand only for white, wealthy men, and their brainwashed women. It shouldn’t have gone with the wind, it should have been razed and burned out of the American psyche.

Maybe one day.

Will I read it again? Probably. I like the way the book changes as I get older. I like noticing things about it that I hadn’t before or that I’d forgotten. And despite its racism, it’s still a good read.

Fascinating insights. Can't say I agree with all of them, as I've only read the book eight times. You know it's difficult to judge others and their attitudes through the lens of our modern world and assuming that we won't look like idiots in a hundred years or so. After all, once upon a time, all the best people threw their feces out the second story windows into the street. But it sure is fun to try. Really good. I enjoyed your take on it – a lot.

Thanks for the image of falling feces! LOL